The last post looked at using various tools to understand why an OCaml 5 program was waiting a long time for IO. In this post, I'll be trying out some tools to investigate a compute-intensive program that uses multiple CPUs.

Table of Contents

- The problem

- ThreadSanitizer

- perf

- mpstat

- offcputime

- The OCaml garbage collector

- statmemprof

- magic-trace

- Tuning GC parameters

- Simplifying further

- perf sched

- olly

- magic-trace on the simple allocator

- perf annotate

- perf c2c

- perf stat

- Conclusions

- Update 2024-08-22

Further discussion about this post can be found on discuss.ocaml.org.

The problem

OCaml 4 allowed running multiple "system threads", but only one can have the OCaml runtime lock, so only one can be running OCaml code at a time. OCaml 5 allows running multiple "domains", all of which can be running OCaml code at the same time (each domain can also have multiple system threads; only one system thread can be running OCaml code per domain).

The ocaml-ci service provides CI for many OCaml programs, and its first step when testing a commit is to run a solver to select compatible versions for its dependencies. Running a solve typically only takes about a second, but it has to do it for each possible test platform, which includes versions of the OCaml compiler from 4.02 to 4.14 and 5.0 to 5.2, multiple architectures (32-bit and 64-bit x86, 32-bit and 64-bit ARM, PPC64 and s390x), operating systems (Alpine, Debian, Fedora, FreeBSD, macos, OpenSUSE and Ubuntu, in multiple versions), etc. In total, this currently does 132 solver runs per commit being tested (which seems too high to me, but let's ignore that for now).

The solves are done by the solver-service, which runs on a couple of ARM machines with 160 cores each. The old OCaml 4 version used to work by spawning lots of sub-processes, but when OCaml 5 came out, I ported it to use a single process with multiple domains. That removed the need for lots of communication logic, and allowed sharing common data such as the package definitions. The code got a lot shorter and simpler, and I'm told it's been much more reliable too.

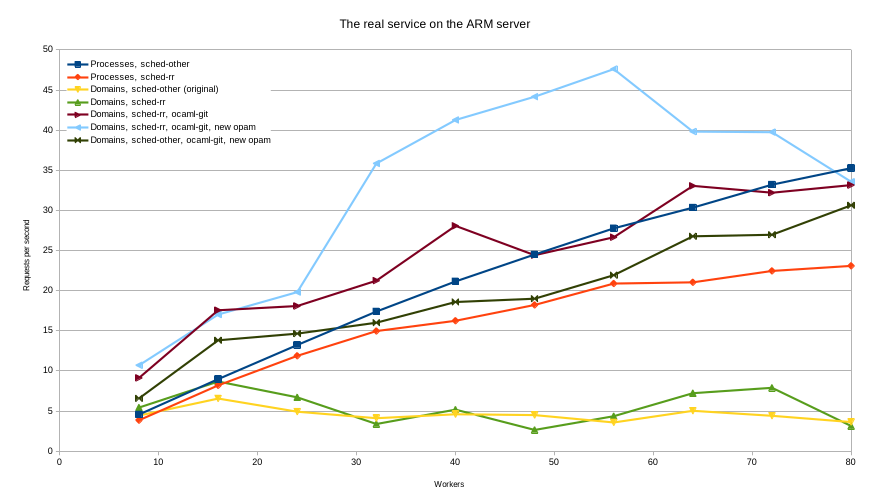

But the performance was surprisingly bad. Here's a graph showing how the number of solves per second scales with the number of CPUs (workers) being used:

The "Processes" line shows performance when forking multiple processes to do the work, which looks pretty good. The "Domains" line shows what happens if you instead spawn domains inside a single process.

Note: The original service used many libraries (a mix of Eio and Lwt ones), but to make investigation easier I simplified it by removing most of them. The simplified version doesn't use Eio or Lwt; it just spawns some domains/processes and has each of them do the same solve in a loop a fixed number of times.

ThreadSanitizer

When converting a single-domain OCaml 4 program to use multiple cores it's easy to introduce races.

OCaml has ThreadSanitizer (TSan) support which can detect these.

To use it, install an OCaml compiler with the tsan option:

$ opam switch create 5.2.0-tsan ocaml-variants.5.2.0+options ocaml-option-tsan

Things run a lot slower and require more memory with this compiler, but it's good to check:

$ ./_build/default/stress/stress.exe --internal-workers=2

[...]

WARNING: ThreadSanitizer: data race (pid=133127)

Write of size 8 at 0x7ff2b7814d38 by thread T4 (mutexes: write M88):

#0 camlOpam_0install__Model.group_ors_1288 lib/model.ml:70 (stress.exe+0x1d2bba)

#1 camlOpam_0install__Model.group_ors_1288 lib/model.ml:120 (stress.exe+0x1d2b47)

...

Previous write of size 8 at 0x7ff2b7814d38 by thread T1 (mutexes: write M83):

#0 camlOpam_0install__Model.group_ors_1288 lib/model.ml:70 (stress.exe+0x1d2bba)

#1 camlOpam_0install__Model.group_ors_1288 lib/model.ml:120 (stress.exe+0x1d2b47)

...

Mutex M88 (0x558368b95358) created at:

#0 pthread_mutex_init ../../../../src/libsanitizer/tsan/tsan_interceptors_posix.cpp:1295 (libtsan.so.2+0x50468)

#1 caml_plat_mutex_init runtime/platform.c:57 (stress.exe+0x4763b2)

#2 caml_init_domains runtime/domain.c:943 (stress.exe+0x44ebfe)

...

Mutex M83 (0x558368b95240) created at:

#0 pthread_mutex_init ../../../../src/libsanitizer/tsan/tsan_interceptors_posix.cpp:1295 (libtsan.so.2+0x50468)

#1 caml_plat_mutex_init runtime/platform.c:57 (stress.exe+0x4763b2)

#2 caml_init_domains runtime/domain.c:943 (stress.exe+0x44ebfe)

...

Thread T4 (tid=133132, running) created by main thread at:

#0 pthread_create ../../../../src/libsanitizer/tsan/tsan_interceptors_posix.cpp:1001 (libtsan.so.2+0x5e686)

#1 caml_domain_spawn runtime/domain.c:1265 (stress.exe+0x4504c4)

...

Thread T1 (tid=133129, running) created by main thread at:

#0 pthread_create ../../../../src/libsanitizer/tsan/tsan_interceptors_posix.cpp:1001 (libtsan.so.2+0x5e686)

#1 caml_domain_spawn runtime/domain.c:1265 (stress.exe+0x4504c4)

...

SUMMARY: ThreadSanitizer: data race lib/model.ml:70 in camlOpam_0install__Model.group_ors_1288

The two mutexes mentioned in the output, M83 and M88, are the domain_lock,

used to ensure only one sys-thread runs at a time in each domain.

In this program we only have one sys-thread per domain and so can ignore them.

The output reveals that the solver used a global variable to generate unique IDs:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

With that fixed, TSan finds no further problems (in this simplified version). This gives us good confidence that there isn't any shared state: TSan would report use of shared state not protected by a mutex, and since the program was written for OCaml 4 it won't be using any mutexes.

That's good, because if one thread writes to a location that another reads then that requires coordination between CPUs, which is relatively slow (though we could still experience slow-downs due to false sharing, where two separate mutable items end up in the same cache line). However, while important for correctness, it didn't make any noticeable difference to the benchmark results.

perf

perf is the obvious tool to use when facing CPU performance problems.

perf record -g PROG takes samples of the program's stack regularly,

so that functions that run a lot or for a long time will appear often.

perf report provides a UI to explore the results:

$ perf report

Children Self Command Shared Object Symbol

+ 59.81% 0.00% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Zeroinstall_solver.Solver_core.do_solve_2283

+ 59.44% 0.00% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Opam_0install.Solver.solve_1428

+ 59.25% 0.00% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Dune.exe.Domain_worker.solve_951

+ 58.88% 0.00% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Dune.exe.Stress.run_worker_332

+ 58.18% 0.00% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Stdlib.Domain.body_735

+ 57.91% 0.00% stress.exe stress.exe [.] caml_start_program

+ 34.39% 0.69% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Stdlib.List.iter_366

+ 34.39% 0.03% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Zeroinstall_solver.Solver_core.lookup_845

+ 34.39% 0.09% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Zeroinstall_solver.Solver_core.process_dep_2024

+ 33.14% 0.03% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Zeroinstall_solver.Sat.run_solver_1446

+ 27.28% 0.00% stress.exe stress.exe [.] Zeroinstall_solver.Solver_core.build_problem_2092

+ 26.27% 0.02% stress.exe stress.exe [.] caml_call_gc

Looks like we're spending most of our time solving, as expected. But this can be misleading. Because perf only records stack traces when the code is running, it doesn't report any time the process spent sleeping.

$ /usr/bin/time ./_build/default/stress/stress.exe --count=10 --internal-workers=7

73.08user 0.61system 0:12.65elapsed 582%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 596608maxresident)k

With 7 workers, we'd expect to see 700%CPU, but we only see 582%.

mpstat

mpstat can show a per-CPU breakdown. Here are a couple of one second intervals on my machine while the solver was running:

$ mpstat --dec=0 -P ALL 1

16:24:39 CPU %usr %sys %iowait %irq %soft %steal %idle

16:24:40 all 78 1 2 1 0 0 18

16:24:40 0 19 1 0 1 0 1 78

16:24:40 1 88 1 0 1 0 0 10

16:24:40 2 88 1 0 1 0 0 10

16:24:40 3 88 0 0 0 0 1 11

16:24:40 4 89 1 0 0 0 0 10

16:24:40 5 90 0 0 1 0 0 9

16:24:40 6 79 1 0 1 1 1 17

16:24:40 7 86 0 12 1 1 0 0

16:24:40 CPU %usr %sys %iowait %irq %soft %steal %idle

16:24:41 all 80 1 2 1 0 0 17

16:24:41 0 85 0 12 1 0 1 1

16:24:41 1 91 1 0 1 0 0 7

16:24:41 2 90 0 0 1 1 0 8

16:24:41 3 89 1 0 1 0 0 9

16:24:41 4 67 1 0 1 0 0 31

16:24:41 5 52 1 0 0 0 1 46

16:24:41 6 76 1 0 1 0 0 22

16:24:41 7 90 1 0 0 0 0 9

Note: I removed some columns with all zero values to save space.

We might expect to see 7 CPUs running at 100% and one idle CPU, but in fact they're all moderately busy. On the other hand, none of them spent more than 91% of its time running the solver code.

offcputime

offcputime will show why a process wasn't using a CPU

(it's like offwaketime, which we saw earlier, but doesn't record the waker).

Here I'm using pidstat to see all running threads and then examining one of the workers,

to avoid the problem we saw last time where the diagram included multiple threads:

$ pidstat 1 -t

...

^C

Average: UID TGID TID %usr %system %guest %wait %CPU CPU Command

Average: 1000 78304 - 550.50 9.41 0.00 0.00 559.90 - stress.exe

Average: 1000 - 78305 91.09 1.49 0.00 0.00 92.57 - |__stress.exe

Average: 1000 - 78307 8.42 0.99 0.00 0.00 9.41 - |__stress.exe

Average: 1000 - 78308 90.59 1.49 0.00 0.00 92.08 - |__stress.exe

Average: 1000 - 78310 90.59 1.49 0.00 0.00 92.08 - |__stress.exe

Average: 1000 - 78312 91.09 1.49 0.00 0.00 92.57 - |__stress.exe

Average: 1000 - 78314 89.11 1.49 0.00 0.00 90.59 - |__stress.exe

Average: 1000 - 78316 89.60 1.98 0.00 0.00 91.58 - |__stress.exe

$ sudo offcputime-bpfcc -f -t 78310 > off-cpu

Note: The ARM machine's kernel was too old to run offcputime, so I ran this on my machine instead,

with one main domain and six workers.

As I needed good stacks for C functions too, I ran stress.exe in an Ubuntu 24.04 docker container,

as recent versions of Ubuntu compile with frame pointers by default.

The raw output was very noisy, showing it waiting in many different places.

Looking at a few, it was clear it was mostly the GC (which can run from almost anywhere).

The output is just a text-file with one line per stack-trace, and bit of sed cleaned it up:

$ sed -E 's/stress.exe;.*;(caml_call_gc|caml_handle_gc_interrupt|caml_poll_gc_work|asm_sysvec_apic_timer_interrupt|asm_sysvec_reschedule_ipi);/stress.exe;\\1;/' off-cpu > off-cpu-gc

$ flamegraph.pl --colors=blue off-cpu-gc > off-cpu-gc.svg

That removes the part of the stack-trace before any of various interrupt-type functions that can be called from anywhere. The graph is blue to indicate that it shows time when the process wasn't running.

There are rather a lot of traces where we missed the user stack.

However, the results seem clear enough: when our worker is waiting, it's in the garbage collector,

calling caml_plat_spin_wait.

This is used to sleep when a spin-lock has been spinning for too long (after 1000 iterations).

The OCaml garbage collector

OCaml has a major heap for long-lived values, plus one fixed-size minor heap for each domain. New allocations are made sequentially on the allocating domain's minor heap (which is very fast, just adjusting a pointer by the size required).

When the minor heap is full the program performs a minor GC, moving any values that are still reachable to the major heap and leaving the minor heap empty.

Garbage collection of the major heap is done in small slices so that the application doesn't pause for long, and domains can do marking and sweeping work without needing to coordinate (except at the very end of a major cycle, when they briefly synchronise to agree a new cycle is starting).

However, as minor GCs move values that other domains may be using, they do require all domains to stop.

Although the simplified test program doesn't use Eio, we can still use eio-trace to record GC events (we just don't see any fibers). Here's a screenshot of the solver running with 24 domains on the ARM machine, showing it performing GC work (not all domains are visible in the picture):

The orange/red parts show when the GC is running and the yellow regions show when the domain is waiting for other domains. The thick columns with yellow edges are minor GCs, while the thin (almost invisible) red columns without any yellow between them are major slices. The second minor GC from the left took longer than usual because the third domain from the top took a while to respond. It also didn't do a major slice before that; perhaps it was busy doing something, or maybe Linux scheduled a different process to run then.

Traces recorded by eio-trace can also be viewed in Perfetto, which shows the nesting better: Here's a close-up of a single minor GC, corresponding to the bottom two domains from the second column from the left:

- The domain triggering the GC (the bottom one here) enters a "stw_leader" (stop-the-world) phase and waits for the other domains to stop.

- One by one, the other domains stop and enter "stw_api_barrier" until all domains have stopped.

- All domains perform a minor GC, clearing their minor heaps.

- They then enter a "minor_leave_barrier" phase, waiting until all domains have finished.

- Each domain returns to running application code.

We can now see why the solver spends so much time sleeping; when a domain performs a minor GC, it spends most of the time waiting for other domains.

(the above is a slight simplification; domains may do some work on the major GC while waiting)

statmemprof

One obvious solution to GC slowness is to produce less garbage in the first place. To do that, we need to find out where the most costly allocations are coming from. Tracing every memory allocation tends to make programs unusably slow, so OCaml instead provides a statistical memory profiler.

It was temporarily removed in OCaml 5 because it needed updating for the new multicore GC, but has recently been brought back and will be in OCaml 5.3. There's a backport to 5.2, but I couldn't get it to work, so I just removed the domains stuff from the test and did a single-domain run on OCaml 4.14. You need the memtrace library to collect samples and memtrace_viewer to view them:

$ opam install memtrace memtrace_viewer

Put this at the start of the program to enable it:

1

| |

Then running with MEMTRACE set records a trace:

$ MEMTRACE=solver.ctf ./stress.exe --count=10

Solved warm-up request in: 1.99s

Running another 10 * 1 solves...

$ memtrace-viewer solver.ctf

Processing solver.ctf...

Serving http://localhost:8080/

The flame graph in the middle shows functions scaled by the amount of memory they allocated.

Initially it showed two groups, one for the warm-up request and one for the 10 runs.

To simplify the display, I used the filter panel (on the left) to show only allocations after the 2 second warm-up.

We can immediately see that OpamVersionCompare.compare is the source of most memory use.

Focusing on that function shows that it performed 54.1% of all allocations. The display now shows allocations performed within it above it (in green), and all the places it's called from in blue below:

The compare function is expensive!

The compare function is expensive!

The bulk of the allocations are coming from this loop:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

It's used when processing a version like 1.2.3 to skip any leading "0" characters

(so that would compare equal to 1.02.3).

The loop function refers to other variables (such as f) from its context,

and so OCaml allocates a closure on the heap to hold these variables.

Even though these allocations are small, we have to do it for every component of every version.

And we compare versions a lot:

for every version of a package that says it requires e.g. libfoo { >= "1.2" },

we have to check the formula against every version of libfoo.

The solution is rather simple (and shorter than the original!):

1 2 3 | |

Removing the other allocations from compare too reduces total memory allocations

from 21.8G to 9.6G!

The processes benchmark got about 14% faster, while the domains one was 23% faster:

A nice optimisation, but using domains is still nowhere close to even the original version with separate processes.

magic-trace

The traces above show the solver taking a long time for all domains to enter the stw_api_barrier phase.

What was the slow domain doing to cause that?

magic-trace lets us tell it when to save the ring buffer and we can use this to get detailed information.

Tracing multiple threads with magic-trace doesn't seem to work well

(each thread gets a very small buffer, they don't stop at quite the same time, and triggers don't work)

so I find it's better to trace just one thread.

I modified the OCaml runtime so that the leader (the domain requesting the GC) records the time.

As each domain enters stw_api_barrier it checks how late it is and calls a function to print a warning if it's above a threshold.

Then I attached magic-trace to one of the worker threads and told it to save a sample when that function got called:

A domain being slow to join a minor GC

A domain being slow to join a minor GC

In the example above,

magic-trace saved about 7ms of the history of a domain up to the point where it entered stw_api_barrier.

The first few ms show the solver working normally.

Then it needs to do a minor GC and tries to become the leader.

But another domain has the lock and so it spins, calling handle_incoming 293,711 times in a loop for 2.5ms.

I had a look at the code in the OCaml runtime. When a domain wants to perform a minor GC, the steps are:

- Acquire

all_domains_lock. - Populate the

stw_requestglobal. - Interrupt all domains.

- Release

all_domains_lock. - Wait for all domains to get the interrupt.

- Mark self as ready, allowing GC work to start.

- Do minor GC.

- The last domain to finish its minor GC signals

all_domains_condand everyone resumes.

I added some extra event reporting to the GC, showing when a domain is trying to perform a GC (try),

when the leader is signalling other domains (signal), and when a domain is sleeping waiting for something (sleep).

Here's what that looks like (in some places):

One sleeping domain delays all the others

One sleeping domain delays all the others

- The top domain finished its minor collection quickly (as it's mostly idle and had nothing to do), and started waiting for the other domains to finish. For some reason, this sleep call took 3ms to run.

- The other domains resume work. One by one, they fill their minor heaps and try to start a GC.

- They can't start a new GC, as the old one hasn't completely finished yet, so they spin.

- Eventually the top domain wakes up and finishes the previous STW section.

- One of the other domains immediately starts a new minor GC and the pattern repeats.

These try events seem useful;

the program is spending much more time stuck in GC than the original traces indicated!

One obvious improvement here would be for idle domains to opt out of GC. Another would be to tell the kernel when to wake instead of using sleeps — and I see there's a PR already: OS-based Synchronisation for Stop-the-World Sections.

Another possibility would be to let domains perform minor GCs independently. The OCaml developers did make a version that worked that way, but it requires changes to all C code that uses the OCaml APIs, since a value in another domain's minor heap might move while it's running.

Finally, I wonder if the code could be simplified a bit using a compare-and-set instead of taking a lock to become leader.

That would eliminate the try state, where a domain knows another domain is the leader, but doesn't know what it wants to do.

It's also strange that there's a state where

the top domain has finished its critical section and allowed the other domains to resume,

but is not quite finished enough to let a new GC start.

We can work around this problem by having the main domain do work too. That could be a problem for interactive applications (where the main domain is running the UI and needs to respond fast), but it should be OK for the solver service. This was about 15% faster on my machine, but appeared to have no effect on the ARM server. Lesson: get traces on the target machine!

Tuning GC parameters

Another way to reduce the synchronisation overhead of minor GCs is to make them less frequent.

We can do that by increasing the size of the minor heap,

doing a few long GCs rather than many short ones.

The size is controlled by the setting e.g. OCAMLRUNPARAM=s=8192k.

On my machine, this actually makes things slower, but it's about 18% faster on the ARM server with 80 domains.

Here are the first few domains (from a total of 24) on the ARM server with different minor heap sizes (both are showing 1s of execution):

The default minor heap size (256k words)

The default minor heap size (256k words)

With a larger minor heap (8192k words)

Note that the major slices also get fewer and larger, as they happen half way between minor slices.

With a larger minor heap (8192k words)

Note that the major slices also get fewer and larger, as they happen half way between minor slices.

Also, there's still a lot of variation between the time each domain spends doing GC (despite the fact that they're all running exactly the same task), so they still end up waiting a lot.

Simplifying further

This is all still pretty odd, though. We're getting small performance increases, but still nothing like when forking. Can the test-case be simplified further? Yes, it turns out! This simple function takes much longer to run when using domains, compared to forking!

1 2 3 4 | |

ref () allocates a small block (2 words, including the header) on the minor heap.

opaque_identity is to make sure the compiler doesn't optimise this pointless allocation away.

Here's what I would expect here:

- The domains all start to fill their minor heaps. One fills it and triggers a minor GC.

- The triggering domain sets an indicator in each domain saying a GC is due. None of the domains is sleeping, so the OS isn't involved in any wake-ups here.

- The other domains check the indicator on their next allocation, which happens immediately since that's all they're doing.

- The GCs all proceed quickly, since there's nothing to scan and nothing to promote (except possibly the current single allocation).

- They all resume quickly and continue.

So ideally the lines would be flat. In practice, we may hit physical limits due to memory bandwidth, CPU temperature or kernel limitations; I assume this is why the "Processes" time starts to rise eventually. But it looks like this minor slow-down causes knock-on effects in the "Domains" case.

If I remove the allocation, then the domains and processes versions take the same amount of time.

perf sched

perf sched record records kernel scheduling events, allowing it to show what is running on each CPU at all times.

perf sched timehist displays a report:

$ sudo perf sched record -k CLOCK_MONOTONIC

^C

$ sudo perf sched timehist

time cpu task name wait time sch delay run time

[tid/pid] (msec) (msec) (msec)

--------------- ------ ------------------------------ --------- --------- ---------

185296.715345 [0000] sway[175042] 1.694 0.025 0.775

185296.716024 [0002] crosvm_vcpu2[178276/178217] 0.012 0.000 2.957

185296.717031 [0003] main.exe[196519] 0.006 0.000 4.004

185296.717044 [0003] rcu_preempt[18] 4.004 0.015 0.012

185296.717260 [0001] main.exe[196526] 1.760 0.000 2.633

185296.717455 [0001] crosvm_vcpu1[193502/193445] 63.809 0.015 0.194

...

The first line here shows that sway needed to wait for 1.694 ms for some reason (possibly a sleep),

and then once it was due to resume, had to wait a further 0.025 ms for CPU 0 to be free. It then ran for 0.775 ms.

I decided to use perf sched to find out what the system was doing when a domain failed to respond quickly.

To make the output easier to read, I hacked eio-trace to display it on the traces.

perf script -g python will generate a skeleton Python script that can format all the events found in the perf.data file,

and I used that to convert the output to CSV.

To correlate OCaml domains with Linux threads, I also modified OCaml to report the thread ID (TID) for each new domain

(it was previously reporting the PID instead for some reason).

Here's a trace of the simple allocator from the previous section:

eio-trace with perf sched data

eio-trace with perf sched data

Note: the colour of stw_api_barrier has changed: previously eio-trace coloured it yellow to indicate sleeping,

but now we have the individual sleep events we can see exactly which part of it was sleeping.

The horizontal green bars show when each domain was running on the CPU.

Here, we see that most of the domains ran until they called sleep.

When the sleep timeout expires, the thread is ready to run again and goes on the run-queue.

Time spent waiting on the queue is shown with a black bar.

When switching to or from another process, the process name is shown.

Here we can see that crosvm_vcpu6 interrupted one of our domains, making it late to respond to the GC request.

Here we see another odd feature of the protocol: even though the late domain was the last to be ready, it wasn't able to start its GC even then, because only the leader is allowed to say when everyone is ready. Several domains wake after the late one is ready and have to go back to sleep again.

The diagram also shows when Linux migrated our OCaml domains between CPUs. For example:

- The bottom domain was initially running on CPU 0.

- After sleeping briefly, it spent a while waiting to resume and Linux moved it to CPU 6 (the leader domain, which was idle then).

- Once there, the bottom domain slept briefly again, and again was slow to wake, getting moved to CPU 7.

Here's another example:

- The bottom domain's sleep finished a while ago, and it's been stuck on the queue because it's on the same CPU as another domain.

- All the other domains are spinning, trying to become the leader for the next minor GC.

- Eventually, Linux preempts the 5th domain from the top to run the bottom domain (the vertical green line indicates a switch between domains in the same process).

- The bottom domain finishes the previous minor GC, allowing the 3rd from top to start a new one.

- The new GC is delayed because the 5th domain is now waiting while the bottom domain spins.

- Eventually the bottom domain sleeps, allowing 5 to join and the GC starts.

I tried using the processor package to pin each domain to a different CPU. That cleaned up the traces a fair bit, but didn't make much difference to the runtime on my machine.

I also tried using chrt to run the program as a high-priority "real-time" task,

which also didn't seem to help.

I wrote a bpftrace script to report if one of our domains was ready to resume and the scheduler instead ran something else.

That showed various things.

Often Linux was migrating something else out of the way and we had to wait for that,

but there were also some kernel tasks that seemed to be even higher priority, such as GPU drivers or uring workers.

I suspect to make this work you'd need to set the affinity of all the other processes to keep them away from the cores being used

(but that wouldn't work in this example because I'm using all of them!).

Come to think of it, running a CPU intensive task on every CPU at realtime priority was a dumb idea;

had it worked I wouldn't have been able to do anything else with the computer!

olly

Exploring the scheduler behaviour was interesting, and might be needed for latency-sensitive tasks, but how often do migrations and delays really cause trouble? The slow GCs are interesting, but there are also sections like this where everything is going smoothly, and minor GCs take less than 4 microseconds:

olly can be used get summary statistics:

$ olly gc-stats './_build/default/stress/stress.exe --count=6 --internal-workers=24'

...

Solved 144 requests in 25.44s (0.18s/iter) (5.66 solves/s)

Execution times:

Wall time (s): 28.17

CPU time (s): 1.66

GC time (s): 169.88

GC overhead (% of CPU time): 10223.84%

GC time per domain (s):

Domain0: 0.47

Domain1: 9.34

Domain2: 6.90

Domain3: 6.97

Domain4: 6.68

Domain5: 6.85

Domain6: 6.59

...

10223.84% GC overhead sounds like a lot but I think this is a misleading, for a few reasons:

- The CPU time looks wrong.

timereports about 6 minutes, which sounds more likely. - GC time (as we've seen) includes time spent sleeping, while CPU time doesn't.

- It doesn't include time spent trying to become a GC leader.

To double-check, I modified eio-trace to report GC statistics for a saved trace:

Solved 144 requests in 26.84s (0.19s/iter) (5.36 solves/s)

...

$ eio-trace gc-stats trace.fxt

./trace.fxt:

Ring GC/s App/s Total/s %GC

0 10.255 19.376 29.631 34.61

1 7.986 10.201 18.186 43.91

2 8.195 10.648 18.843 43.49

3 9.521 14.398 23.919 39.81

4 9.775 16.537 26.311 37.15

5 8.084 10.635 18.719 43.19

6 7.977 10.356 18.333 43.51

...

24 7.920 10.802 18.722 42.30

All 213.332 308.578 521.910 40.88

Note: all times are wall-clock and so include time spent blocking.

It ran slightly slower under eio-trace, perhaps because recording a trace file is more work than maintaining some counters, but it's similar. So this indicates that with 24 domains GC is taking about 40% of the total time (including time spent sleeping).

But something doesn't add up, on my machine at least:

- With processes, the simple allocator test's main process spends 2% of its time in GC and takes 2.4s to run.

- With domains, the main domain spends 20% of its time in GC and takes 8.2s.

Even if that 20% were removed completely, it should only save 20% of the 8.2s. So with domains, the code must be running more slowly even when it's not in the GC.

magic-trace on the simple allocator

I tried running magic-trace to see what it was doing outside of the GC. Since it wasn't calling any functions, it didn't show anything, but we can fix that:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

Here we do blocks of 100 allocations in a function called foo.

The annotations are to ensure the compiler doesn't inline it.

The trace was surprisingly variable!

magic-trace of foo between GCs

magic-trace of foo between GCs

I see times for foo ranging from 50ns to around 750ns!

Note: the extra foo call above was probably due to a missed end event somewhere.

perf annotate

I ran perf record on the simplified version:

1 2 3 4 | |

Here the code is simple enough that we don't need stack-traces (so no -g):

$ sudo perf record ./_build/default/main.exe

$ sudo perf annotate

│ camlDune__exe__Main.foo_273():

│ mov $0x3,%eax

0.04 │ cmp $0xc9,%rax

│ ↓ jg 39

7.34 │ d: sub $0x10,%r15

13.37 │ cmp (%r14),%r15

0.09 │ ↓ jb 3f

0.21 │16: lea 0x8(%r15),%rbx

70.26 │ movq $0x400,-0x8(%rbx)

6.66 │ movq $0x1,(%rbx)

0.73 │ mov %rax,%rbx

0.00 │ add $0x2,%rax

0.01 │ cmp $0xc9,%rbx

0.66 │ ↑ jne d

0.28 │39: mov $0x1,%eax

0.34 │ ← ret

0.00 │3f: → call caml_call_gc

│ ↑ jmp 16

The code starts by (pointlessly) checking if 1 > 100 in case it can skip the whole loop. After being disappointed, it:

- Decreases

%r15(young_ptr) by 0x10 (two words). - Checks if that's now below

young_limit, callingcaml_call_gcif so to clear the minor heap. - Writes 0x400 to the first newly-allocated word (the block header, indicating 1 word of data).

- Writes 1 to the second word, which represents

(). - Increments the loop counter and loops, unless we're at the end.

- Returns

().

Looks like we spent most of the time (77%) writing the block, which makes sense.

Reading young_limit took 13% of the time, which seems reasonable too.

If there was contention between domains, we'd expect to see it here.

The output looked similar whether using domains or processes.

perf c2c

To double-check, I also tried perf c2c.

This reports on cache-to-cache transfers, where two CPUs are accessing the same memory,

which requires the processors to communicate and is therefore relatively slow.

$ sudo perf c2c record

^C

$ sudo perf c2c report

Load Operations : 11898

Load L1D hit : 4140

Load L2D hit : 93

Load LLC hit : 3750

Load Local HITM : 251

Store Operations : 116386

Store L1D Hit : 104763

Store L1D Miss : 11622

...

# ----- HITM ----- ------- Store Refs ------ ------- CL -------- ---------- cycles ---------- Total cpu Shared

# RmtHitm LclHitm L1 Hit L1 Miss N/A Off Node PA cnt Code address rmt hitm lcl hitm load records cnt Symbol Object Source:Line Node

...

7 0 7 4 0 0 0x7f90b4002b80

----------------------------------------------------------------------

0.00% 100.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0x0 0 1 0x44a704 0 144 107 8 1 [.] Dune.exe.Main.foo_273 main.exe main.ml:7 0

0.00% 0.00% 25.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0x0 0 1 0x4ba7b9 0 0 0 1 1 [.] caml_interrupt_all_signal_ main.exe domain.c:318 0

0.00% 0.00% 25.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0x0 0 1 0x4ba7e2 0 0 323 49 1 [.] caml_reset_young_limit main.exe domain.c:1658 0

0.00% 0.00% 25.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0x8 0 1 0x4ce94d 0 0 0 1 1 [.] caml_empty_minor_heap_prom main.exe minor_gc.c:622 0

0.00% 0.00% 25.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0x8 0 1 0x4ceed2 0 0 0 1 1 [.] caml_alloc_small_dispatch main.exe minor_gc.c:874 0

This shows a list of cache lines (memory addresses) and how often we loaded from a modified address.

There's a lot of information here and I don't understand most of it.

But I think the above is saying that address 0x7f90b4002b80 (young_limit, at offset 0) was accessed by these places across domains:

main.ml:7(ref ()) checks againstyoung_limitto see if we need to call into the GC.domain.c:318sets the limit toUINTNAT_MAXto signal that another domain wants a GC.domain.c:1658sets it back toyoung_triggerafter being signalled.

The same cacheline was also accessed at offset 8, which contains young_ptr (address of last allocation):

minor_gc.c:622setsyoung_ptrtoyoung_endafter a GC.minor_gc.c:874adjustsyoung_ptrto re-do the allocation that triggered the GC.

This indicates false sharing: young_ptr only gets accessed from one domain but it's in the same cache line as young_limit.

The main thing is that the counts are all very low, indicating that this doesn't happen often.

I tried adding an incr x on a global variable in the loop, and got some more operations reported.

But using Atomic.incr massively increased the number of records:

| Original | incr | Atomic.incr | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Load Operations | 11,898 | 25,860 | 2,658,364 |

| Load L1D hit | 4,140 | 15,181 | 326,236 |

| Load L2D hit | 93 | 163 | 295 |

| Load LLC hit | 3,750 | 3,173 | 2,321,704 |

| Load Local HITM | 251 | 299 | 2,317,885 |

| Store Operations | 116,386 | 462,162 | 3,909,500 |

| Store L1D Hit | 104,763 | 389,492 | 3,908,947 |

| Store L1D Miss | 11,622 | 72,667 | 550 |

See C2C - False Sharing Detection in Linux Perf for more information about all this.

perf stat

perf stat shows statistics about a process.

I ran it with -I 1000 to collect one-second samples.

Here are two samples from the test case on my machine,

one when it was running processes and one while it was using domains:

$ perf stat -I 1000

# Processes

8,032.71 msec cpu-clock # 8.033 CPUs utilized

2,475 context-switches # 308.115 /sec

51 cpu-migrations # 6.349 /sec

44 page-faults # 5.478 /sec

35,268,665,452 cycles # 4.391 GHz

48,673,075,188 instructions # 1.38 insn per cycle

9,815,905,270 branches # 1.222 G/sec

48,986,037 branch-misses # 0.50% of all branches

# Domains

8,008.11 msec cpu-clock # 8.008 CPUs utilized

10,970 context-switches # 1.370 K/sec

133 cpu-migrations # 16.608 /sec

232 page-faults # 28.971 /sec

34,606,498,021 cycles # 4.321 GHz

25,120,741,129 instructions # 0.73 insn per cycle

5,028,578,807 branches # 627.936 M/sec

24,402,161 branch-misses # 0.49% of all branches

We're doing a lot more context switches with domains, as expected due to the sleeps, and we're executing many fewer instructions, which isn't surprising. Reporting the counts for individual CPUs gets more interesting though:

$ sudo perf stat -I 1000 -e instructions -Aa

# Processes

1.000409485 CPU0 5,106,261,160 instructions

1.000409485 CPU1 2,746,012,554 instructions

1.000409485 CPU2 14,235,084,764 instructions

1.000409485 CPU3 7,545,940,906 instructions

1.000409485 CPU4 2,605,655,333 instructions

1.000409485 CPU5 6,023,131,238 instructions

1.000409485 CPU6 2,860,656,865 instructions

1.000409485 CPU7 8,195,416,048 instructions

2.001406580 CPU0 5,674,686,033 instructions

2.001406580 CPU1 2,774,756,912 instructions

2.001406580 CPU2 12,231,014,682 instructions

2.001406580 CPU3 8,292,824,909 instructions

2.001406580 CPU4 2,592,461,540 instructions

2.001406580 CPU5 7,182,922,668 instructions

2.001406580 CPU6 2,742,731,223 instructions

2.001406580 CPU7 7,219,186,119 instructions

3.002394302 CPU0 4,676,179,731 instructions

3.002394302 CPU1 2,773,345,921 instructions

3.002394302 CPU2 13,236,080,365 instructions

3.002394302 CPU3 5,142,640,767 instructions

3.002394302 CPU4 2,580,401,766 instructions

3.002394302 CPU5 13,600,129,246 instructions

3.002394302 CPU6 2,667,830,277 instructions

3.002394302 CPU7 4,908,168,984 instructions

$ sudo perf stat -I 1000 -e instructions -Aa

# Domains

1.002680009 CPU0 3,134,933,139 instructions

1.002680009 CPU1 3,140,191,650 instructions

1.002680009 CPU2 3,155,579,241 instructions

1.002680009 CPU3 3,059,035,269 instructions

1.002680009 CPU4 3,102,718,089 instructions

1.002680009 CPU5 3,027,660,263 instructions

1.002680009 CPU6 3,167,151,483 instructions

1.002680009 CPU7 3,214,267,081 instructions

2.003692744 CPU0 3,009,806,420 instructions

2.003692744 CPU1 3,015,194,636 instructions

2.003692744 CPU2 3,093,562,866 instructions

2.003692744 CPU3 3,005,546,617 instructions

2.003692744 CPU4 3,067,126,726 instructions

2.003692744 CPU5 3,042,259,123 instructions

2.003692744 CPU6 3,073,514,980 instructions

2.003692744 CPU7 3,158,786,841 instructions

3.004694851 CPU0 3,069,604,047 instructions

3.004694851 CPU1 3,063,976,761 instructions

3.004694851 CPU2 3,116,761,158 instructions

3.004694851 CPU3 3,045,677,304 instructions

3.004694851 CPU4 3,101,053,228 instructions

3.004694851 CPU5 2,973,005,489 instructions

3.004694851 CPU6 3,109,177,113 instructions

3.004694851 CPU7 3,158,349,130 instructions

In the domains case all CPUs are doing roughly the same amount of work. But when running separate processes the CPUs differ wildly! Over the last 1-second interval, for example, CPU5 executed 5.3 times as many instructions as CPU4. And indeed, some of the test processes are finishing much sooner than the others, even though they all do the same work.

Setting /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpufreq/policy*/energy_performance_preference to performance didn't make it faster,

but setting it to power (power-saving mode) did make the processes benchmark much slower,

while having little effect on the domains case!

So I think what's happening here with separate processes is that the CPU is boosting the performance of one or two cores at a time, allowing them to make lots of progress.

But with domains this doesn't happen, either because no domain runs long enough before sleeping to trigger the boost, or because as soon as it does it needs to stop and wait for the other domains for a GC and loses it.

Conclusions

The main profiling and tracing tools used were:

perfto take samples of CPU use, find hot functions and hot instructions within them, record process scheduling, look at hardware counters, and find sources of cache contention.statmemprofto find the source of allocations.eio-traceto visualise GC events and as a generic canvas for custom visualisations.magic-traceto see very detailed traces of recent activity when something goes wrong.ollyto report on GC statistics.bpftracefor quick experiments about kernel behaviour.offcputimeto see why a process is sleeping.

I think OCaml 5's runtime events tracing was the star of the show here, making it much easier to see what was going on with GC,

especially in combination with perf sched.

statmemprof is also an essential tool for OCaml, and I'll be very glad to get it back with OCaml 5.3.

I think I need to investigate perf more; I'd never used many of these features before.

Though it is important to use it with offcputime etc to check you're not missing samples due to sleeping.

Unlike the previous post's example, where the cause was pretty obvious and led to a massive easy speed-up, this one took a lot of investigation and revealed several problems, none of which seem very easy to fix. I'm also a lot less confident that I really understand what's happening here, but here is a summary of my current guess:

- OCaml applications typically allocate lots of short-lived values.

- With a single domain this isn't much of a problem; minor GCs are fast. With multiple domains however we have to wait for every domain to enter the GC, and then wait again for them all to exit.

- This can be very fast (4 microseconds or so per GC), but if one domain is late due to OS scheduling then it can be much longer (several ms in some cases).

- When a domain needs to wait for another it spins for a bit and then sleeps. If the other domain runs on the same CPU then spinning delays it from running. On the other hand, sleeping introduces longer delays and can cause the CPU to slow down.

- Idle domains are currently expensive. An idle domain requires a syscall to wake it, and often causes all the other domains to sleep waiting for it. When the idle domain does wake, it still can't start the GC and has to wait again for the leader.

- If the leader gets suspended while holding the lock, all the other domains will spin waiting for it (without ever sleeping). This time isn't accounted for in the GC events reported by OCaml 5.2.

Since the sleeping mechanism will be changing in OCaml 5.3, it would probably be worthwhile checking how that performs too. I think there are some opportunities to improve the GC, such as letting idle domains opt out of GC after one collection, and it looks like there are opportunities to reduce the amount of synchronisation done (e.g. by letting late arrivers start the GC without having to wait for the leader, or using a lock-free algorithm for becoming leader).

For the solver, it would be good to try experimenting with CPU affinity to keep a subset of the 160 cores reserved for the solver. Increasing the minor heap size and doing work in the main domain should also reduce the overhead of GC, and improving the version compare function in the opam library would greatly reduce the need for it. And if my goal was really to make it fast (rather than to improve multicore OCaml and its tooling) then I'd probably switch it back to using processes.

Finally, it was really useful that both of these blog posts examined performance regressions, so I knew it must be possible to go faster. Without a good idea of how fast something should be, it's easy to give up too early.

Anyway, I hope you found some useful new tool in these posts!

Update 2024-08-22

I reported above that using chrt to make the process high priority didn't help on my machine.

It also didn't help on the ARM server using the real service.

However, it did help a lot when running the simplified version of the solver on the ARM server!

Some more investigation showed that the real service had an additional problem:

it spawned a git log subprocess after every solve, and this was causing all the domains to pause

for about 50ms during the fork operation.

Use OCaml code to find the oldest commit

eliminated the problem (and is also faster, as it can cache the history, although that doesn't matter much).

Here are some benchmarks of various combinations of fixes:

-

Processes, sched-otheris the original version using multiple processes. Oddly, usingsched-rrto make it high-priority actually slows this one down! -

Domains, sched-otheris the original version using domains. The results are noisy but usingsched-rrdoesn't seem to help. -

ocaml-gitindicates that thegit logsubprocess has been replaced by OCaml code. -

new opamindicates using the latest Git version of the opam library, which includes my Reduce allocations in opamVersionCompare as well as Kate's Speedup OpamVersionCompare by 25%.

And with that, the new multicore solver service is finally faster than the old process-based one!